El Faro first published this essay in Spanish in August 2021. It has been translated for The Tertulia, a monthly space for academia to investigate and debate Central America.

In May 1889, President Francisco Menéndez approved a new regulatory framework for El Salvador’s primary public school system. The new rules included the introduction of a Military Exercises program, which would be compulsory for all students in first through sixth grade.

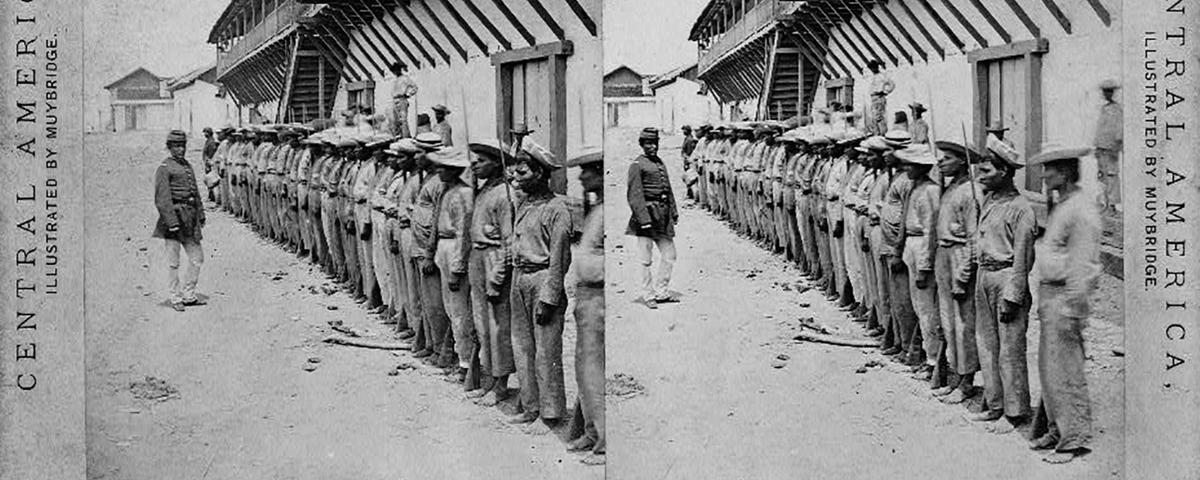

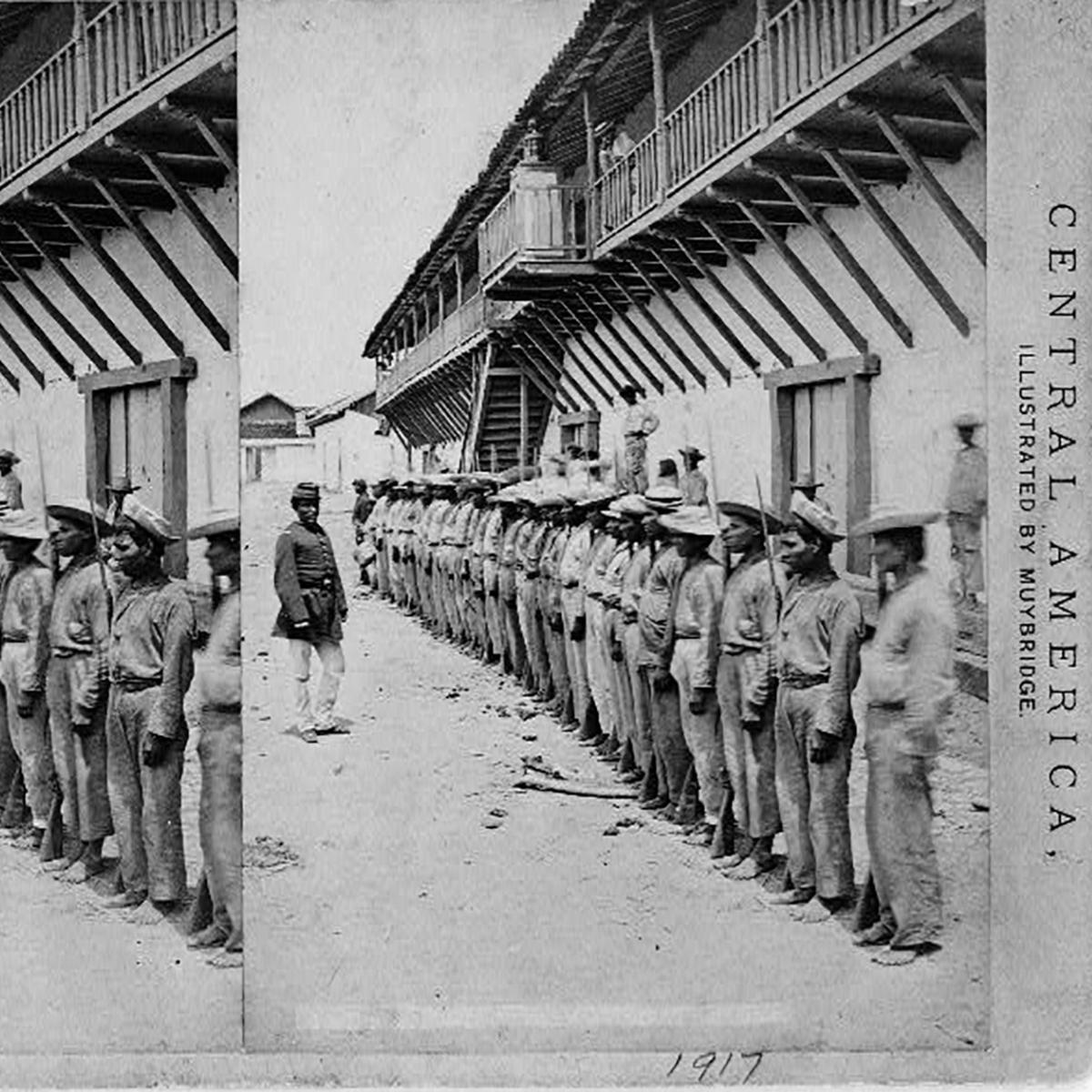

In early 1890, the Salvadoran government presented the public education supervisor for the departments of Cabañas and Chalatenango, Felipe Solano, with 300 composition notebooks, 200 arithmetic notebooks, 50 sheets of blotting paper, seven world maps, and 21 maps of El Salvador, specifically for use in Cabañas. Solano also received, among other supplies, 50 wooden rifles, no doubt intended for military training exercises.

Nineteenth-century El Salvador had fostered a political culture that was anchored in authoritarianism, the “revolution” of the caudillos, coups, and wars. The rifle defined much of the political history of the republic.

With the implementation of the new mandatory Military Exercises course track, the Menéndez government opened the door of the country’s schools to this authoritarian and militaristic political culture. Previous administrations, such as the Gerardo Barrios and Santiago González governments, had flirted with military instruction in schools, but it was Menéndez who fully and explicitly institutionalized it.

As far as can be ascertain from a review of the official government gazette, Diario Oficial, military drills remained compulsory in El Salvador’s schools until the early 1910s. The last revised regulations establishing these exercises as a curricular requirement were approved by President Fernando Figueroa in September 1908.

In the Eyes of Maximiliano, Everyone Was an Enemy

Below are excerpts from two texts on military training published at the time that Francisco Gavidia was appointed head of the General Directorate of Public Education.

On February 22, 1896, following the resignation of Alberto Masferrer from the position, which he had assumed on February 4, 1895, President Rafael Antonio Gutiérrez assigned the responsibility to Gavidia. Gavidia reduced the number of required course subjects from 22 to nine, and the number of grade levels from six to three. Course subject nine was titled Gymnastics and Military Exercises.

In April of that year, 1896, Gavidia revived La Nueva Enseñanza, a magazine that circulated between 1887 and 1890 under the direction of a group of Colombian intellectuals —Víctor Dubarry, Francisco Gamboa, Justiniano Núñez, and Marcial Cruz— who had participated in the educational reforms enacted during the presidency of Francisco Menéndez. The first set of drills, “Lessons in Military Tactics”, published in Gavidia’s new issue “for the schools of the Republic”, began as follows (translated from the Spanish):

MILITARY TACTICS — The art of arranging, moving, and employing troops on the battlefield with order, speed, and mutual protection, combining them according to the nature of their weapons, the conditions of the terrain, and the dispositions of the enemy. Tactics relevant to a single weapon are considered specific tactics.

The body of the child was conceived as the soldier of tomorrow. Thus, from an early age, kids were expected to learn proper posture, martial cadence, and battlefield tactics, their bodies trained in the logic of the weapon, their minds molded to think in terms of combat zones and to imagine an enemy. Students would be taught to understand themselves as a collective, to be the troops of the nation, and to fight against its enemies.

In its May 1896 issue, La Nueva Enseñanza published a text titled “Civic Education” (corresponding to the course subject with the same name) by French author Jules Steeg. In the second part of the article, under the title “Civic Duties,” the author states the following:

We owe the state not only our money and our time, but also, if necessary, our lives. The state requires an army, comprised of every citizen capable of bearing arms, to defend the country against foreign aggression. Everyone must pay this tribute to their country and serve for the period of time designated by law. This is what military service means. When one loves his country passionately, he does not suffer the years he spends under the shadow of its flag. In the army, one does not enjoy every freedom he might want, but later, he will recall with joy and pride his time spent in uniform.

Lastly, there is a civic duty, a duty that only exists in free countries, which corresponds to the right to vote, whereby every citizen exercises the functions of the sovereign, by appointing their representatives. A citizen has a duty never to abstain, but to vote intelligently, conscientiously, and freely. One of the greatest mistakes that can be made is to vote at random, out of weakness or fear, and at the risk of relinquishing the government of the city, or of the entire country, to wrongdoers. But there is something even worse: to sell your suffrage for favors or money. The right to vote is sacred; one must vote without being swayed by deference, and neither should one be influenced by intimidation or corruption. A good citizen’s vote should be inspired only by patriotism.

Ever since 1880, Rafael Zaldívar’s government had been committed to developing a secular school system. The void left by the eradication of Christian doctrine from educational curricula, however, was soon filled by a new kind of belief system: civic religiosity. Now, children were expected to dedicate their lives to the state, and the best way to do this was through military service. To love one’s country was to love weapons, and to be prepared to go to battle. For the sake of love and service, one had to fight the nation’s (imaginary) enemies. Public schools became institutions that extolled military discipline, the rituals of military service, the use of weapons, and war as a principle of action or reaction on the part of the state. To go to school was to be summoned to be a soldier of the republic.

Contrary to the idealistic tone of Jules Steeg’s article on military service and the right to vote, in 20th-century El Salvador, the military class was one of the primary obstacles preventing the country from pursuing a process of democratization, with free elections, a plurality of political parties, and a genuine alternation in governance.

What began as the pedagogy of the rifle became terror at gunpoint, states of siege, the suspension of constitutional guarantees, political persecution, arrests, torture, disappearance, and civil war. The state took up arms against its enemies, imaginary or real, internal or external. War that was imagined and practiced in the schools.

Julián González is a professor of history and philosophy at the Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas.